By Dr. Mariana Vargas-Caballero

During a Master’s research project, students are often at a pivotal point. They’ve built expertise and developed advanced skills, their data is fresh, and their engagement with the project is at its peak. Yet, once the dissertation work concludes, that momentum is lost.

Bringing research outputs, like publication-quality figures, to completion often requires extra focused work. However, continuing research beyond the degree often depends on students being able to contribute their time without financial support, something not everyone can manage. Without a compensated opportunity, valuable work may be left incomplete, and talented students may miss out on important work experience.

Creating the Early Career Research Incubator

To address this issue, I’ve been developing a practical model within my lab since 2018. While I’m still refining the name, I currently refer to it as the Early Career Research Incubator. The idea is simple: if a student’s research has more to give, why should it stop at graduation?

Instead, students are offered a paid extension (typically six to twelve weeks) as formal work experience at the University of Southampton. This provides time and support to polish research outputs in a structured and compensated environment.

To date, I’ve supported six students through this model, including two who participated during their degree by contributing to lab work with their skills in areas outside their project. During their time in the Incubator, students have completed figures, contributed to publications or grant proposals, networked at conferences, and gained critical experience for job or PhD interviews in prestigious centres including the University of Southampton. This practice follows university employment policies and ensures that students are appropriately compensated for their time and expertise.

Why Post-Degree Support Matters

The Incubator treats graduates, and near graduates, as emerging professionals whose contributions deserve both credit and compensation. It recognises what students already know and can do.

It also directly addresses a long-standing issue in academic culture: the reliance on informal or unpaid work on top of the degree. By offering formal roles, we remove the expectation that students will “volunteer” to wrap up research or help with tasks not associated directly with their project, and instead create fair, ethical pathways for them to continue contributing and developing.

Case study

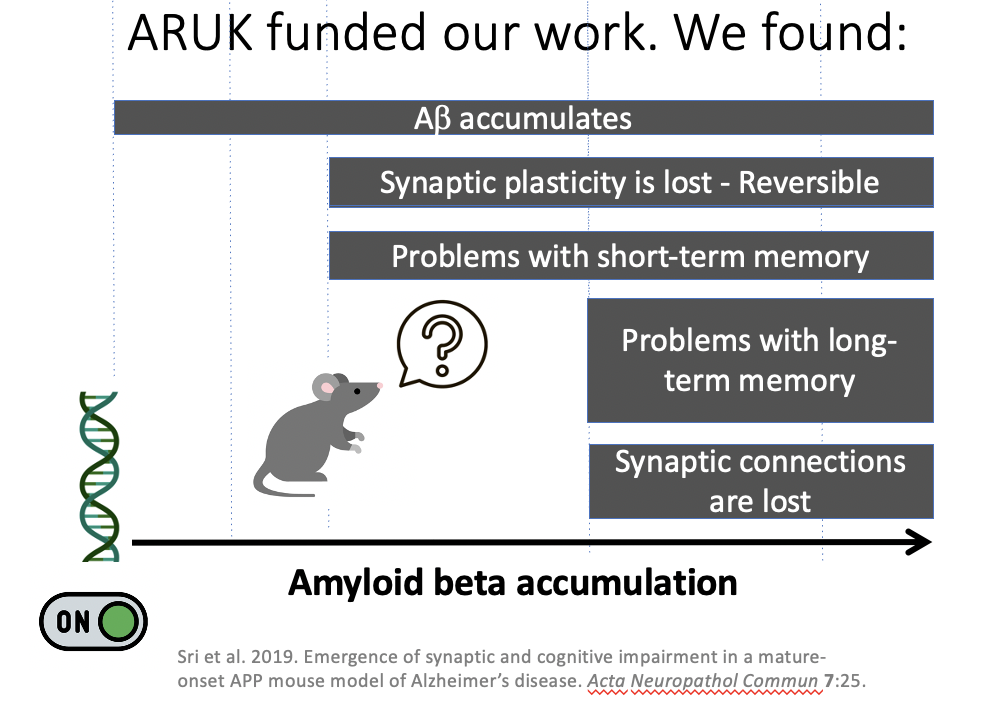

In summer 2023, Natasha Lebos, an International student at the University of Southampton, completed a six-week Summer Internship in the Vargas-Caballero lab, funded by the Alzheimer’s Research UK South Coast Network, following her Integrated Masters (MSc) in Neuroscience.

“I found the time invaluable. The extra weeks gave me the opportunity to gain confidence and feel independent. The studentship also helped me prepare for life as a PhD student, easing the transition from undergraduate to postgraduate. I am very grateful for the time spent working alongside the other PhD students in Mariana’s lab and learning techniques from her and other academics. I thoroughly enjoyed the experience and believe it has had a very positive impact on my career and abilities as a developing researcher.”

During her internship, Natasha applied her existing skills in cell culture, transfection, and imaging, and expanded these by conducting live assays, including antibody “feeding” experiments. Her work has provided essential insights and preliminary data for new lab projects aimed at understanding fundamental synapse biology and the mechanisms underlying schizophrenia.

Cultural Impact

Perhaps the most encouraging outcome of this practice has been seeing the model adopted by colleagues who have already introduced similar practices in their labs, adapting the approach to fit their teams and disciplines.

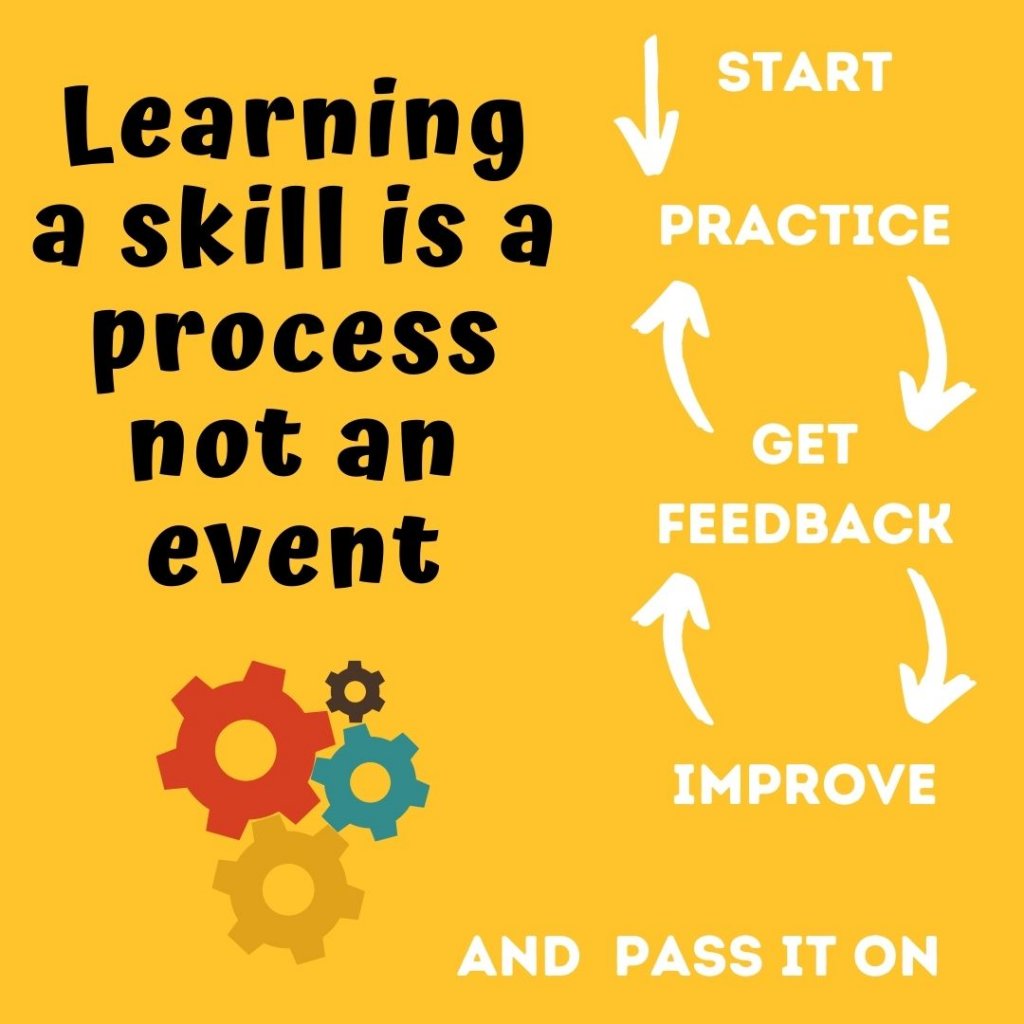

These small shifts in structure can lead to meaningful cultural change in our academic spaces making them more inclusive and supportive. The Incubator is not about finishing projects, it’s about building confidence, reinforcing skills, and offering a soft landing between student life and a research career.

Looking Ahead

This approach is scalable, it has an immediate impact on student’s CVs as added relevant work experience, and its relatively straightforward to implement. If we want to improve research culture, we don’t always need grand reforms. We can use existing structures such as paying real living wages or ideally higher wages in line with the work done, and utilise existing recruitment systems for short-term assignments that works together with work experience at the University of Southampton. Similar systems exist in other Universities.

Obviously, we need a budget to support such initiatives, and funding for this sort of position is limited. That is because most of the summer studentships are aimed at supporting students in the middle of their degree (e.g. end of their second year). These are excellent but we need to think differently for support beyond the dissertation. For this reason, I am now costing for a paid internship per year whenever I apply for a grant. For students, a paid role like this can be the first real bridge between study and the next step of their career. I am privileged for playing a role in that process.